“Go confidently in the direction of your dreams. Live the life you have imagined.”

When I think about my father I appreciate he always supported my dream to be a writer. He encouraged and praised me. He was the first person to show me how powerful, amazing and entertaining the English language can be. He introduced me to many brilliant and effective authors and poets, but most of all he believed in my desire and need to write.

Although a flawed man with many personal demons he truly loved his family. When I discovered a notebook of his after he died my tears were for his lost dreams as I read poems, snippets of stories and even a short play.

As my older sister Cate said at Dad’s funeral, ‘who knows what dad could have achieved if he’d had educational opportunities and economic freedom to make choices…’ Like many of his generation who lived through the Great Depression and WW2, he never went to high school and always chased money to survive, and support his family.

However, he did go to night school, he did constantly improve himself no matter what job he had and he was a prime example of someone with a thirst for knowledge, who educated himself. Education was the key to success as far as Dad was concerned. We must study hard at school and not waste ‘the talents God gave you’. No doubt the regrets he felt at his own failure to stay engaged with the school system coloured his attitude.

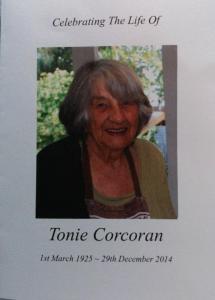

Today, the tenth anniversary of his death, I reflect on how glad I am that he was my Dad and be grateful for the gifts he gave me and the memories I choose to honour.

“Why am I compelled to write? . . . Because the world I create in the writing compensates for what the real world does not give me. By writing I put order in the world, give it a handle so I can grasp it…”

August 25, 2005

The air carries the smell of spring, but it will be some hours before the sun provides daylight and any warmth. I make an effort to peer into the night with weary and moist eyes. The raucous laughter of kookaburras breaks the stillness – an echo triggering memories of childhood days spent at Croydon in the 1960s. Kookaburras swooped down and stole our cat’s dinner, the raw kangaroo meat an irresistible and easy meal. The birds returned to the trees their laughter like petals blown in the wind.

Tonight the birds swoop from tree to tree, searching for breakfast or perhaps a late supper, their demeanour similar to a hawk. It is 4.00am. Are they congratulating each other on a successful hunt, or have they spotted prey? The hospital grounds and car parks studded with trees may provide what the birds seek. If not, the mini forest stretching north towards Belgrave like a thick, mottled green tablecloth undoubtedly holds enough scurrying mammals to keep the kookaburras laughing for some time.

I can’t recall the last time I heard a kookaburra in Mordialloc where I have lived for twenty-one years. Close to the sea, the gulls are prevalent, but because of the prolonged drought, it is more likely the squealing of rosellas and harsh caws of wattlebirds and ravens demanding or complaining at the lack of food.

I look from the window of Room 2 East Ward on the second floor of William Angliss Hospital, in the aptly named Melbourne suburb, of Ferntree Gully. The shadows of the night change shape to become recognisable objects. There is solace in the ordinariness of the scene – a maintenance worker parks his car and toolbox in hand disappears into the bowels of a building I assume houses the hospital generator. Nurses travel between the adjacent nurses’ home and the main hospital; navy cardigans clasped around shoulders, the only indication there is an early morning chill to the air.

I press my legs against the wall radiator, but the artificial warmth of hot water pipes will not relieve the coldness I feel. I want to open the window wide and scream, ‘Don’t you know my father is dying?’ Nothing has prepared me for this night, even although it is barely three years since I farewelled my husband, John. You can never prepare or become used to losing someone you love. Death is indeed the last frontier. I grip the windowsill realising the harsh reality of day may deliver a cruel blow.

The nurse turned down the wall radiator earlier in the evening with no noticeable cooling of the room apart from the removal of body heat when others in the family left just before midnight. The dodgy heater a bit like Dad’s health the last few years: sometimes okay, other times difficult to know if operating well. The intermittent work of his pancreas made his diabetes almost impossible to regulate. So many years he struggled with diabetes – a terrible sentence for someone with a sweet tooth and robust appetite.

The softness of Dad’s hands as I held them a few minutes ago lingers on my skin. Hands, once dry, calloused worker’s hands transformed soft and smooth despite the accumulated wrinkles of 83 years. Stretched over arthritic bones, his fragile skin, like precious parchment. The paleness almost transparent, belying his olive complexion inherited from the survivors of the wrecked sixteenth century Spanish Armada intermarrying with the inhabitants of Scotland’s west coast islands. Well, that’s the mythology still hotly debated by historians. I can hear Dad’s voice disparagingly saying, ‘but what do academics know.’ He was a great storyteller and as Robert McKee teaches, it’s all about the power of story!

The memory of our trip to Australia in 1962, on the migrant ship SS Orion, makes me smile. The ship picked up 500 Greek migrants at Piraeus and after a few days in the Mediterranean sun, the Greek passengers approached my sun-tanned Dad thinking he was Greek. How could this olive-skinned man, sporting coal black hair and moustache be Scottish! For the rest of the voyage, they tried to strike up conversations. ‘Sorry Jimmy,’ said Dad like a typical Glaswegian, ‘don’t know yir lingo.’

The subdued lighting of the hospital room dulls the age and sun spots, mottling the backs of his hands. The marks fade into insignificance on his thin muscle-wasted arms. When younger and stronger, and employed as a ‘boy wakener,’ he knocked the doors of sleeping drivers with those hands at a time when working class people didn’t own watches or clocks and there were no telephones for early morning wake up calls.

As a fireman, he shovelled 5 tonnes of coal a day into the ferocious flames of a steam train’s furnace. As a locomotive driver, he manipulated train controls and signals and became a diesel instructor and acting depot foreman during a twenty-five-year career with British Rail. In Australia, Dad worked at many semi-skilled jobs as he chased money for his family during a further twenty-seven years driving. His arms steering everything from petrol tankers, delivery vans, trucks, tractors, forklifts, buses, utilities, and station wagons.

He never went to high school, but when it came to a car engine he could revive and fix motors others would abandon to the wrecker’s yard. I picture him wiping oily hands on a cloth or his dungarees. I’ve never driven a car but surprise myself with the mechanical knowledge absorbed from endless conversations between Dad and my brothers.

I remember as a little girl in Scotland waiting for my dad’s train to pass by the house. Whenever he drove the steam engine he nicknamed “Ivanhoe” he would blow the whistle loudly just as he rounded the bend. In the distance, we could see his once snowy white handkerchief appear as a tiny speck amongst the belching smoke and steam as he gathered speed for the hill before him. We knew he could see the bed sheet we frantically waved with Mum’s help from the upstairs bedroom window because another long-drawn blast which sounded like “Ivanhoe, oh, oh,o …” echoed throughout the valley.

Younger, stronger arms cuddled a wife and six children, ten grandchildren and embraced four step-grandchildren when they joined the clan. How I ache for those arms to hold me close once more, to make me feel safe. Dad always fearless, his strength, a refuge. He took on bullies in the workplace, bullies in the street. His slightly misshapen nose testimony to defending a stranger from would-be muggers, teaching a scab a lesson on worker solidarity and corralling a bull that escaped in the rail-yards. A trophy of fights he could have done without, but Dad often as game as a dozen commandos.

I rub my thumb along his; trace the outline of his nail. His fingernails, longer than I recall, strong and manicured – testimony to the attentive personal care received in the nursing home where he has lived as a dementia patient for the last seven years.

Strangers cut his nails, bathe him, trim his hair and moustache, and even wipe his bottom. I remember, his fingernails never long but always clean. Scrubbed to remove the embedded coal dust when he was a railwayman in Scotland. Scrubbed even harder to be rid of engine oil with his first job in Australia of petrol tanker driver and then a serviceman for Exide Batteries. Over the years, scrubbing removed a variety of debris from his many blue-collar occupations, including pottery dust and garden soil.

Yet, Dad’s hands were much gentler than Mum’s – not the skin, but his touch. He was the one who washed wounds gently, dabbed calamine lotion on even the tiniest mosquito bite or chickenpox blister. Perhaps, if he had not been the youngest of thirteen children and denied the opportunity for further education, he may have been a doctor. His dedication to self-education at night school and constant thirst for knowledge proved he had the intellectual capacity.

A moan reminds me that Dad is still in this world. His laboured breathing eases to an almost gentle rhythmic snore. I sit in the uncomfortable visitor’s chair, grateful my sister, Rita left a large curved pillow squashed to support a back beginning to ache with tension and lack of comfortable sleep.

Dad’s slack-jaw repose, unsettling. Awed at his vulnerability, I remember a man with an explosive temper, yet the patience to teach and to learn. Now he lies helpless at the mercy of a hospital system that sees him as a nuisance. A dying old man, taking a bed and resources more useful to younger, fitter others. I relive the argument between my brother George and the Charge Nurse earlier in the day when they tried to convince us Dad should be discharged and sent back to the nursing home. Our system has a lot to learn about dying and grief.

An unwanted patient here, Dad showed much patience in his life. He spent hours to find an intermittent fault on electrical equipment or the origin of an unusual noise in a car or motorbike engine. More hours in makeshift darkrooms developing black and white photographs until the best possible copy was printed. He often shared a useful or attractive object produced from leftover scrap wood from off-cuts in the bargain bin outside the local hardware shop. His photographic and developing skills, his expertise with cars and motorbikes and his DIY talents all passed on to his children with varying success.

To be a good provider for his wife and children and to be a good parent his driving force. He never appeared hesitant making the tough decisions once we were capable of understanding and contributing. He laid down rules about our social life, the friends we chummed with, insisted we apply ourselves at school and take responsibility for chores in and out of the home. Robust arguments about the length of my brother’s hair in the 60s, when my sisters and I could start ‘dating’, our behaviour at school and at home all memories that fade into insignificance in comparison to the years he sacrificed to keep us healthy and safe.

The Protestant work ethic and the Church of Scotland shaped much of Dad’s thinking, but also socialist writers like Robert Tressell who wrote, The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists and he identified not only with the poetry of Robert Burns but the imperfect man. We grew up with Burns’ quotations ringing in our ears and all of us can recite verses, especially the ones with moral and ethical points! Dad admired politicians like Keir Hardie and the Bevan brothers. Papa had bought Tressell’s book for Dad to read, and Dad encouraged his children to read it. I bought copies for my daughters.

I change the cassette tape that is playing softly in the background. Rabbie Burns poetry set to music or songs he has written. Scottish singers as diverse as Duncan Macrae, Andy Stewart, Kenneth McKellar, the Alexander Brothers and The Corries singing their hearts out

I flick through the box of tapes brought from the nursing home. Each song or artist stirs memories of family celebrations or other occasions. I picture Dad working in his shed happily ‘making sawdust’ as he referred to his woodworking hobby. Or he’s reclining in his armchair, a glass of brandy (or a good malt whisky when he felt flush), not far from his hand. He loved his music and the advancements in technology from old 78s to vinyl LPs; reel to reel to cassette tapes – all marvellous inventions in his eyes. Unfortunately, with the onset of dementia, he missed the proliferation of CDs – and I can’t conjure an image of him with an iPod or MP3 player either – his hearing aids would get in the way and I think he’d be a vocal critic of social media! ‘If someone wants to talk to me let them say it to my face, or pick up the phone!’

When diagnosed with Tinnitus in the 70s his love of playing music intensified as he tried to block the constant noises and ringing in his ears. He used alcohol too and became someone else, his personality forever damaged by attempts to cure this cruel byproduct of industrial deafness and medication after the Hong Kong Flu. I recall the pain in his eyes when he read a poem of mine about Bermagui where I referred to ‘the silence of nature’.

‘Oh, what I’d give for silence,’ he murmured through tears.

A gurgling erupts from Dad’s throat and his brow furrows. He screws his eyes even more tightly shut and pulls his knees up towards his chest and moans. I remember the stabbing pains of early labour and assume his frail body is experiencing waves of uneven pain. I shiver. Is that the scent of death on his breath? I know medication and his lack of sustenance are probably causing the unusual sweet/sour smell, but fear freezes my heart.

I stand up to seek out a nurse when the door creaks open and two nurses on night duty tiptoe into the room. I chatted with these friendly women at the beginning of their shift. They have no problem with my family’s determination to ensure one or more of Dad’s kinfolk will be with him until the end and are not surprised to see me.

The small dark-skinned nurse came from a family of eight and trained in England, ‘We just want to turn your Dad and check how he is going.’

The grey-haired nurse with a Queensland drawl worked as a relief sister in Dad’s first nursing home. She speaks with familiarity, ‘We’ll just give George a bit of a sponge and change.’

‘Thank you,’ I whisper. ‘He appears to be in a bit of pain… writhing around.’

The other nurse flicks through Dad’s chart, ‘No problem, we’ll give him something for the pain.’

‘Yes,’ agrees the Queenslander leaning over to take his pulse, ‘we’ll look after your dad, don’t worry.’

Kenneth MacKellar is singing ‘Keep right on to the end of the road’ and my heart begins to race.

Ev’ry road thro’ life is a long, long road,

Fill’d with joys and sorrows too,

As you journey on how your heart will yearn

For the things most dear to you.

With wealth and love ’tis so,

But onward we must go.Keep right on to the end of the road,

Keep right on to the end,

Tho’ the way be long, let your heart be strong,

Keep right on round the bend.

I desperately need fresh air. ‘I’ll just go outside for a few minutes,’ I stutter. The nurses nod their approval.

Outside I stare at the sky and try to identify Orion – the shapeshifter that to me is a saucepan – and the Southern Cross. If I can see them, the world will be okay because for as long as I can remember since moving to Australia, I have always searched the night sky for those constellations. I breathe in the eucalyptus air. A dark shape swoops. Kookaburras laugh.

Who am I trying to fool? My world will never be the same again. I realise I’ve been crying and dab away the tears before returning to resume my vigil. It will be daylight soon and my sister Cate will come to relieve me, but I know I will not leave Dad – not just yet.