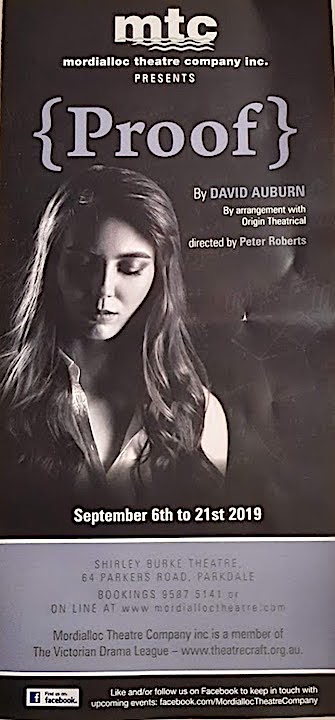

Shirley Burke Theatre’s Current Production

Last night, my friend and fellow scribe, Lisa Hill attended our local theatre to enjoy {PROOF} by playwright, director and screenwriter, David Auburn. It’s a drama I’d recommend and you only have another week to grab a seat!

This is one of the best productions I’ve attended since Lisa invited me to be her ‘play buddy’ and buy a yearly ticket to Shirley Burke’s 2019 series. Other reviews of ones I’ve enjoyed this year are here and here.

Now officially an aged pensioner supporting local theatre a joyful pastime and helps ensure an accessible art scene in Kingston. There have been several mixed outings this year: some scripts and/or acting better than others, but last night was a triumph for the actors and an interesting script.

The prize-winning play written two decades ago raises relevant and timeless issues, explores the human condition to provide that all-important conflict necessary for memorable art.

{PROOF} examines family relationships, sibling rivalry, the stress of being a carer, grief, mental illness, hereditary disease, gender equality, the fine line between brilliance and madness, and most importantly, trust and its importance for a healthy relationship!

The title, encased in parentheses alludes to the mathematical motif running through the plot and characters.

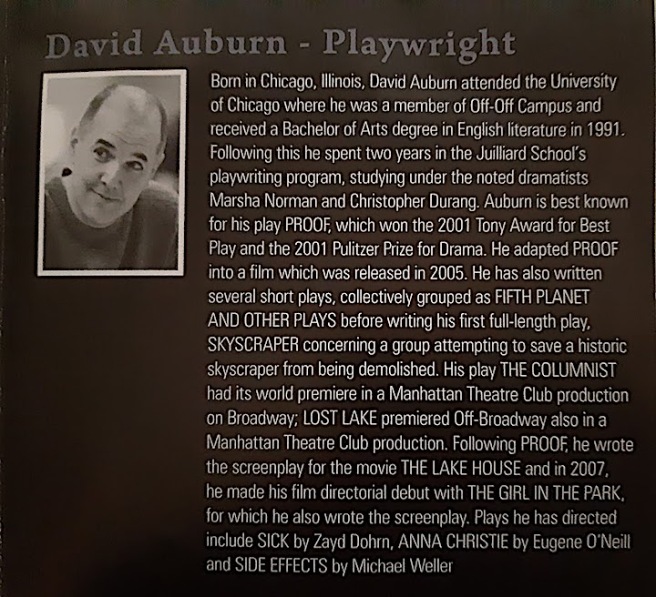

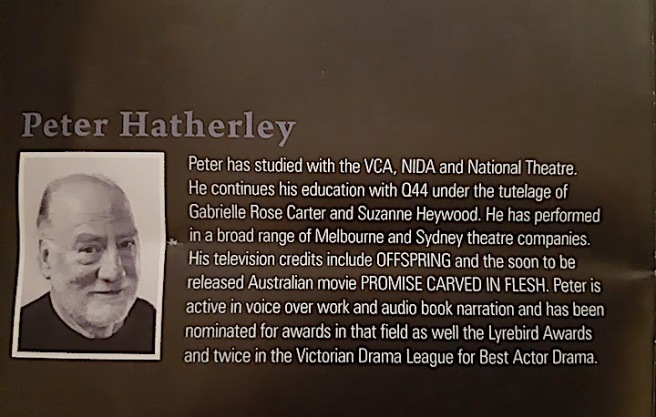

One of the four characters, Robert (Peter Hatherley), is a mathematics genius suffering an indeterminate mental illness – not an easy role to play but he handles it well.

Hal (Chris Hill) an ex-student of Robert’s is going through Robert’s notebooks hoping to discover another great mathematical theory, Catherine (JaneLeckie), Robert’s daughter has inherited his genius and perhaps his mental illness – a fear alluded to and voiced.

A notebook with a new groundbreaking theory becomes the centre of contention causing conflict between Hal and Catherine, and Catherine and her sister Claire (Samantha Stone).

Who wrote the entries and when? How do you establish authenticity? Who will gain from the notebook’s contents?

Jokes about maths geeks dispelling their nerdy image of being plain, boring or weird provide several laughs in a play tackling the fragility and frailty of the human mind, body, and spirit.

Serendipity or Coincidence?

Yesterday was R U OK Day? with all forms of media and health bodies promoting increased awareness of mental health. Mental illness was a strong theme in the play with the character, Robert suffering an unnamed condition. The audience learns he often disconnects from reality and displays paranoia.

I doubt I was alone in seeing the similarity between Robert’s psychosis and that of John Forbes Nash, diagnosed with schizophrenia and played by Russell Crowe in the movie, A Brilliant Mind.

Both characters portrayed as brilliant mathematicians but in {PROOF} the audience is left wondering about Robert’s illness …

… the oft-quoted line by Oscar Levant (1906-1972) springs to mind, “There’s a fine line between genius and insanity. I have erased this line.”

Another theme explored in the play is the role of carers and with an ageing population, regardless of whether healthy or sick, it’s a hot topic.

Do you care at home or put the person in an institution? What is the toll on the carer? Catherine has sacrificed her education and career to look after father, Robert. A sacrifice her sister Claire didn’t agree with and it is Claire who pays the bills for the upkeep of the house and Robert’s care.

Several poignant scenes in the play occur when the sisters, Catherine and Claire (Samantha Stone) argue about the wisdom of keeping Robert at home and whether the fragile Catherine needs to be cared for if she has inherited her father’s ‘condition’ – whatever that is – and Claire’s insistence Catherine return with her to New York after the father’s funeral so the house can be sold.

There were several scenes where anger demanded and all the actors were persuasive in their portrayals coming across as authentic, which can be hard to do with extreme emotions.

Catherine goes through the full gamut of emotions and Jane Leckie did a superb job with a minimum of make-up – her facial expressions and body language captured grief, fear, anger, disappointment, sadness, distrust, playfulness and joy – to the extent when final bows were made with her hair loose and a beaming smile it could have been a different person on stage!

Peter Hatherley’s, Robert suitably mercurial and feisty using the space on stage to good effect with expansive gestures hinting at his younger self’s confident brilliance and older self’s celebratory status but unsteady at times to remind us of his illness.

Plenty in this play to feed private reflection and reminiscing about family responsibilities, loyalty and relationships, the opportunities and positions available for women in academia, the strain of caring for those you love when they become unlovable, and the profound, debilitating, and often unpredictable effects of grief.

The Gender Card & Generational Divide

Bearing in mind, the play is 20 years old, you don’t expect an exploration of the recent complex debates around gender to be a major theme, but there is a strong acknowledgement of the omission of ‘herstory’ in {PROOF}.

Debates on important issues demand lots of conversations in the community and it’s no secret that for years the sciences excluded women. The situation resulting in efforts to address school curriculums, and increased encouragement of women to study mathematics and associated fields.

The issue is dealt with on stage with an interesting conversation between Hal and Catherine both in their twenties, both maths geeks, both quirky and socially awkward in their own way. The underlying romantic tension between the pair an interesting sub-story and the physical and verbal interactions between them believable and well-executed by Jane Leckie and Chris Hill.

The play tackles the generational divide with Hal suggesting maths is ‘a young man’s game’, and even Robert mentions it is important to achieve early success to compete.

Hal reveals attending conferences and observing drug use (alcohol and LSD) and that some older men need a drug like Speed to keep their mind sharp and racing because of fears creativity has peaked in their early twenties!

Robert’s illness started in his mid-twenties and Hal who is twenty-eight fears the chance to be as brilliant and famous as Robert has passed him by. However, if he can decipher Robert’s notebooks and perhaps discover something new… perhaps produce that great leap of the mind and experimentation that renders mathematicians awesome.

Hal believes all creative mathematicians who come up with original work are men, especially young men who are at their peak in their early twenties, but after probing by Catherine acknowledges there was a woman at Stanford University, he can’t remember her name.

‘Sophie Germain?’ Catherine suggests.

Hal pauses for a moment as if remembering, and replies, ‘…I’ve probably seen her at meetings, but haven’t met her…’

‘She was born in Paris in 1776,’ is Catherine’s droll comment.

‘So I’ve definitely met her,’ Hal replies with a grin.

Amidst this humour, Catherine delivers a lesson on Sophie Germain surviving the French Revolution’s Terror by hiding in her father’s study and reading. Later, formal education denied because she was a female, she furthered her education by personal study but only got noticed for her work on prime numbers when she corresponded with learned men under the male pseudonym, Antoine August Le Blanc.

Catherine explained how her father gave her the book about Sophie to read and encouraged her to study – another hint that she shared her father’s love, perhaps obsession of math.

Hal admits his ignorance and stupidity – he has studied Germain Primes.

There is an exchange of numbers, equations and sums in their conversation similar to one Catherine had with her father at the beginning of the play and Hal starts to understand Catherine has talent, but as if threatened, he stops adding and extending figures and instead queries if Sophie’s ruse was ever discovered by Gauss, the most famous of her correspondents.

Catherine recites a long passage from a letter she has memorised where Gauss recognised the extraordinary talents of Sophie and her difficulties and courage revealing her genius to a world dominated by men.

Hal’s reaction is to kiss Sophie and then apologise for being ‘ a little drunk’!

The budding romance between Catherine and Hal is a roller-coaster ride in the play – trust shattered along with Catherine’s composure when Hal doubts her honesty and even seems to go along with Claire’s suggestion that Catherine is mentally unstable.

The kindled romance dissolved by an explosive row, reignited in an uneasy truce, perhaps understanding and acceptance, but we are left to write their future.

Stagecraft & Setting

The various set designs I’ve seen this year at Shirley Burke have been impressive – the team who build the sets deserve congratulations. It is a small intimate theatre, therefore, the stage has limitations, yet they ‘come up trumps’ every time.

Like a short story, nothing in a play, including set and props, must be there unless it advances the plot or contributes to the storyline.

{PROOF} is yet another play set in the USA but thankfully the American accents did not jar as much as earlier plays this year.

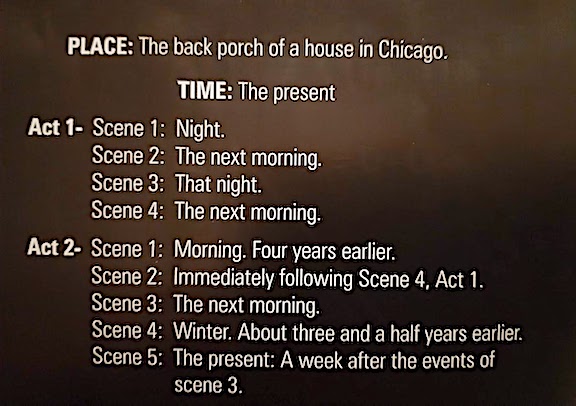

Every scene is set on the back verandah (porch) of a house near the University of Chicago where Robert’s genius is revered and where he taught before his initial ‘breakdown’ and later descent into ill health.

The confined space is not glamorous and a scattering of dead leaves suggests autumn and in another scene winter – a metaphor for Robert’s ageing and death? The need for regrowth and change? Catherine’s sacrifice and confinement for years as she cared for her father, but a promise of better things to come?

Playwriting like screenwriting is a collaborative art, for results you require the sets, actors, lighting, sound, stagecraft and direction to gel … this production of {PROOF} ticks all the boxes.

The drabness of the porch relieved by the glimpse of the interior of the house through glass doors and at Robert’s wake the light is suitably bright accompanied by party music so we get a sense there are others inside.

Scene changes are heralded by various mood-appropriate music, the most memorable being a discordant, noisy band number after Hal admits he is with a group of fellows from the math department who play in a bar. Their signature act called ‘i’ lower case and they stand without playing anything for three minutes.

A math joke which Catherine guesses, ‘Imaginary Number?’

There are successful flashback scenes too (and a ghost scene, when grieving Catherine ‘talks’ to her father after his death).

These are often difficult to deliver effectively on stage and can be confusing for an audience to follow, but are handled well.

Like all good dramas, Act 1 ends with a shock announcement, which gave us plenty to talk about over Interval!

An Irrelevant Aside?

It’s interesting what actions resonate with members of an audience.

The play opens with twenty-five-year-old Catherine curled asleep in a chair on the verandah. Her father, Robert wakes her up – it has just gone midnight and now officially her birthday. He has a bottle of champagne, which she insists on popping because last time he broke a window! (The first chuckle/laugh in the play.)

Catherine pops the champagne cork like a waitress serving at a high table keeping the cork under control. She proceeds to swig at the contents while conversing with her father who we learn has been unwell but now believes he is okay and is convincing her to return to study.

Because of my lived experience waitressing throughout university student days in Canberra and later travelling in Scotland, I know how to open a bottle of champagne in a confined space without letting a wayward cork hit a person or an object and yet still retain that satisfying “POP” everyone expects. It is an acquired skill, so well done Jane Leckie for not hitting a member of the cast or audience!

Another memorable moment in the play is when Hal discovers a page in one of Robert’s notebooks where he recognizes Catherine has kept him from being institutionalised (what Claire wanted) and has saved his life by caring for him. ‘Where does her strength come from? I can never repay her?’

My father had dementia and was eventually institutionalised for his own and my mother’s safety but in his lucid moments, he often uttered similar sentiments.

When the play ended, the audience gave well-deserved extended applause and Lisa and I both agreed it has been the best production we have seen this year.

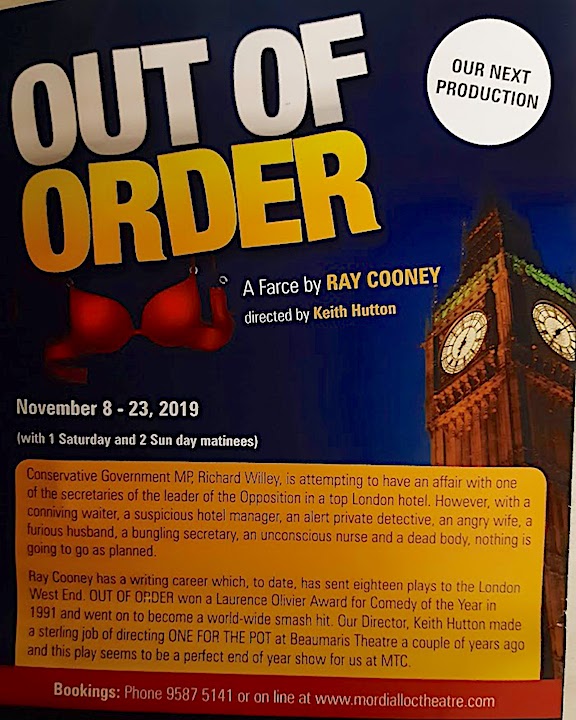

I picked up a flyer advertising the next production and considering the shenanigans in the UK (is life imitating art?) it seems a timely production to end the year with a few belly laughs and the absurdities of ‘the human condition’.

If you can’t get to see {PROOF} perhaps book early to be “Out of Order‘!